But the cork house project by Matthew Barnett Howland with Dido Milne and Oliver Wilton is not an example of pursuing a subjective idea or an indulgence of patronage. The architects have, as an independent initiative, analysed an old material and explored modern ways of using it, as a didactic offering to the construction industry.

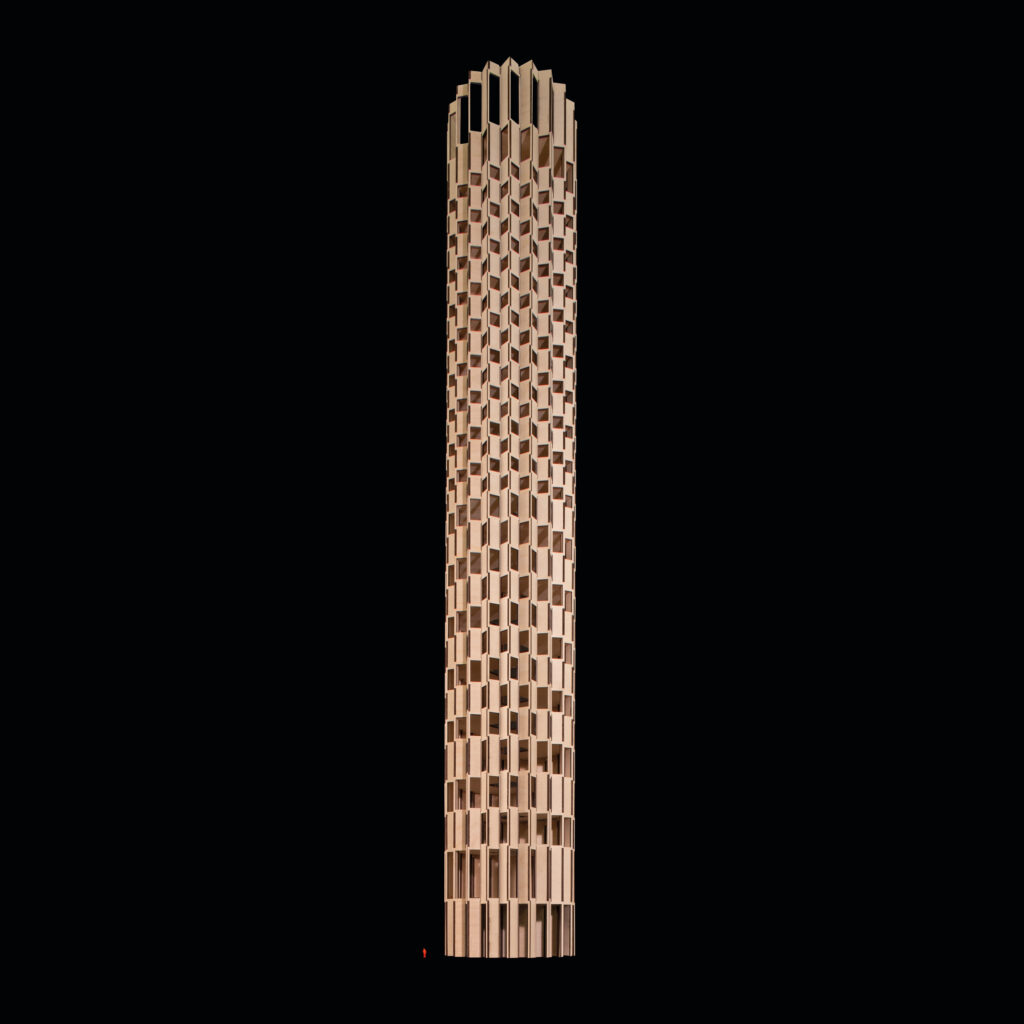

Cork House is not merely clad in cork externally, insulated with cork invisibly, or lined in cork internally. Several examples of deploying cork to improve the thermal performance or character of a more conventional construction exist around the world, and particularly in Portugal, home of the cork oak tree. But this is a house made almost entirely of cork. I make this distinction as an advocate of timber architecture in a market sated with rhetorical examples of ‘timber buildings’ which are actually a steel or concrete frame clad in wood, or a timber structure clad in brick. With global construction materials and methods increasingly criticised for carbon emissions, here is a unique example of an experimental house using only the bark of cork oak trees as a solid structure, insulation and finish, inside and out.