Why did you choose this book?

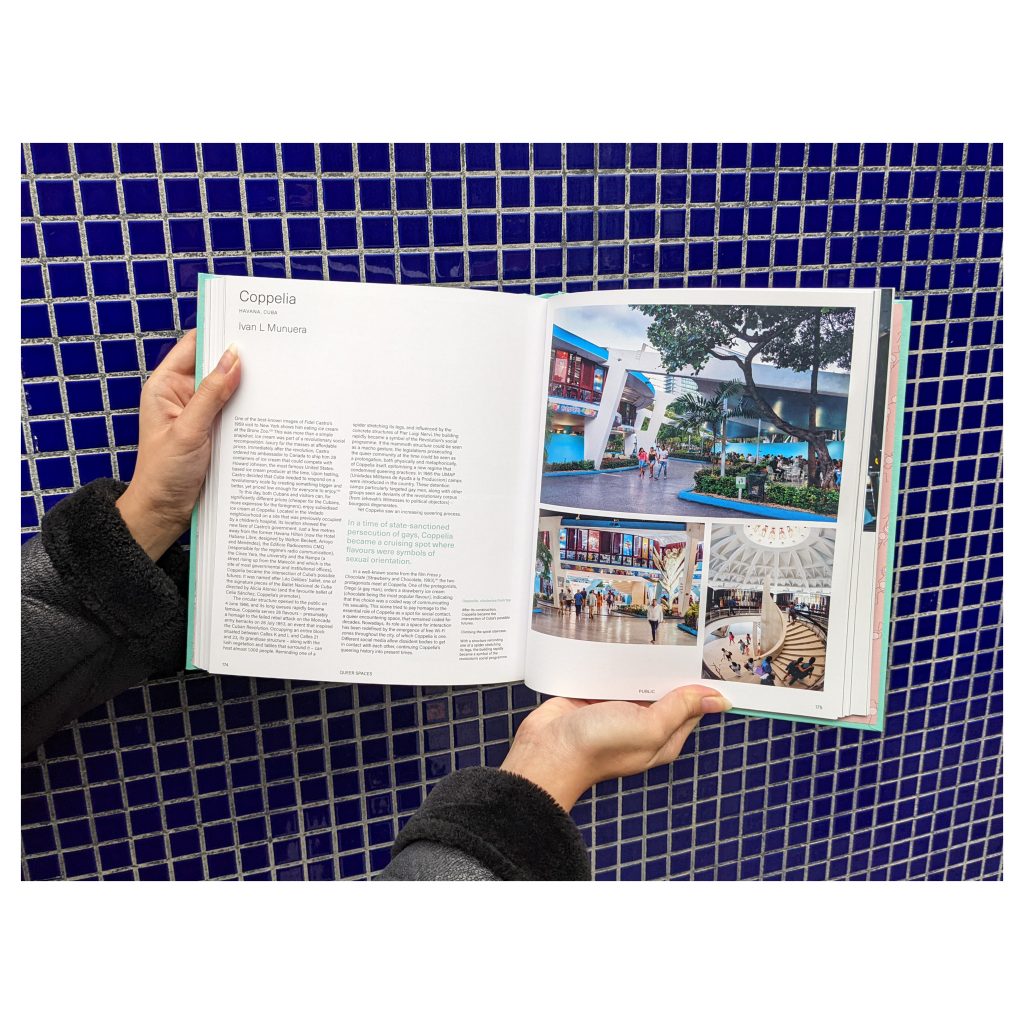

I chose to read the book as it is an atlas charting different queer spaces globally. I haven’t come across any books that have done that before. It is significant for that reason. In a sense, it goes beyond being a book and becomes a network that provides details of other queer people in architecture.

The book raises awareness. As a queer person, you are already isolated. In academia, when studying architecture and defining your approach to design briefs, people are informed by spaces that are relevant to their own experiences. Typically, there are lots of academic texts that validate these experiences. To design a queer space as part of an academic architecture programme, you are missing precedents, you can refer to queer discourse in the arts, but that conceptualises your project. This book provides tangible queer space case studies. It is of major significance that a book like this has only just been published in 2022. It shows how, despite the fact we are in the 21st century and we feel we can talk about topics openly, there are many things that remain closeted.

The book speaks for a variety of queer identities. The start and end of the book focuses on positive and negative experiences of being queer and the way queer people might experience space. It gives the example of a trans person leaving their house and putting their make-up on because it is something they cannot do at home. I was worried that the book would focus on the experience of being a white gay male, as that can be a dominant perspective, but it is a collaborative text, it does its best to reach out to different communities across the world. It addresses intersectionality by covering the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre in London acknowledging the fact you can be black, queer, and non-binary.